This post is part of Kavya Jain’s 2023 Global Food Fellowship. You can also learn more about her knead 2 know presentation from October 2023 here.

I spent the summer in New Mexico and New Haven, digging through artist and literary archives and interviewing artists, poets, farmers, and cooks. My research question was about the possibilities of meals as sites of poetic and political imagination, and I studied both artist sociality and the artistic nature of food processes. Functionally, I asked, where did food lie in the creative processes of art makers?

My project emerged from discovering a relationship between painter Georgia O’Keeffe and poet Mei-mei Berssenbrugge, both artists in rural New Mexico. Berssenbrugge lives and writes in Abiquiu where she also worked for O’Keeffe, spending weekends at her home sharing meals. My project stemmed from my curiosity about those meals, their contents, and their relations to each artist’s production but specifically poetics.

In New Mexico, I worked in the Georgia O’Keeffe Archives, reading through O’Keeffe’s cookbooks and understanding her relationship to food. Many are interested in O’Keeffe’s specific domestic order with its custom furniture and features, calling her home her biggest piece of art. She hired staff to cook, garden, and held an interest in nutrition, eating simply, seasonally and peculiarly for her time. Though O’Keeffe has the reputation of being a “maker” she really was just a person with strong preferences, aesthetic sensibility and the ability to pay staff to execute her visions, culinary and otherwise. What were the labor politics of this?

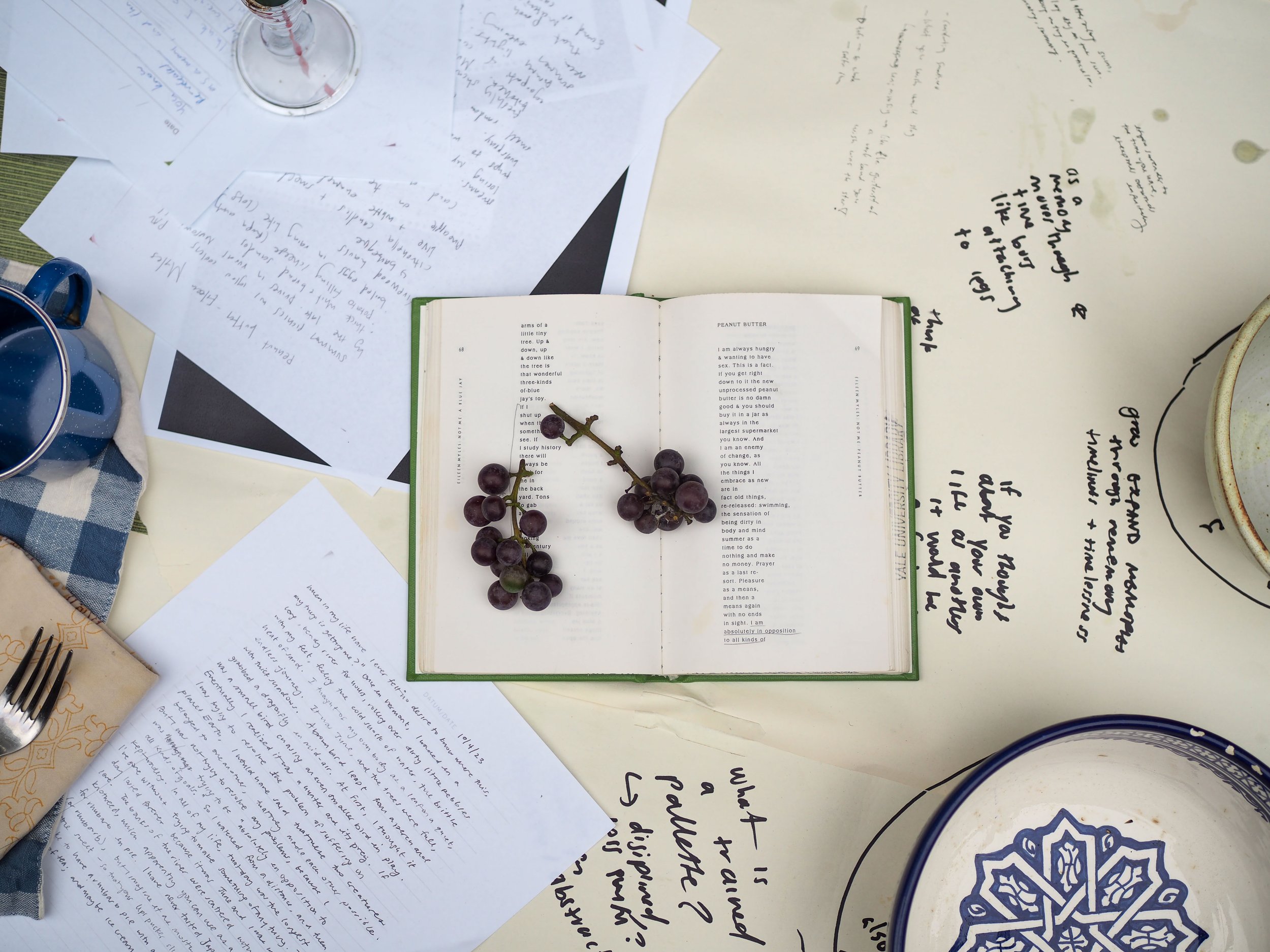

Meanwhile, in conversation with Bersenbrugge and her literary archives in the Beinecke, food was not discussed as part of the creative process but an inhibitor to it. Berssenbrugge’s papers revealed an incompatibility between writing and food. Her conflicted relationship prevented her from her actual work: poetry. Speaking with Berssenbrugge, I considered her generational and gendered context as a woman tied to the second generation New York School. Perhaps to be taken seriously as a woman writer demanded that one disavow domesticity and prevent a victory of “life” over work. Misogyny dictated the relationship between artistic and domestic labor for many women and perhaps made it difficult for some to see the kitchen as a site of art, transcendence and intellectual rigor.

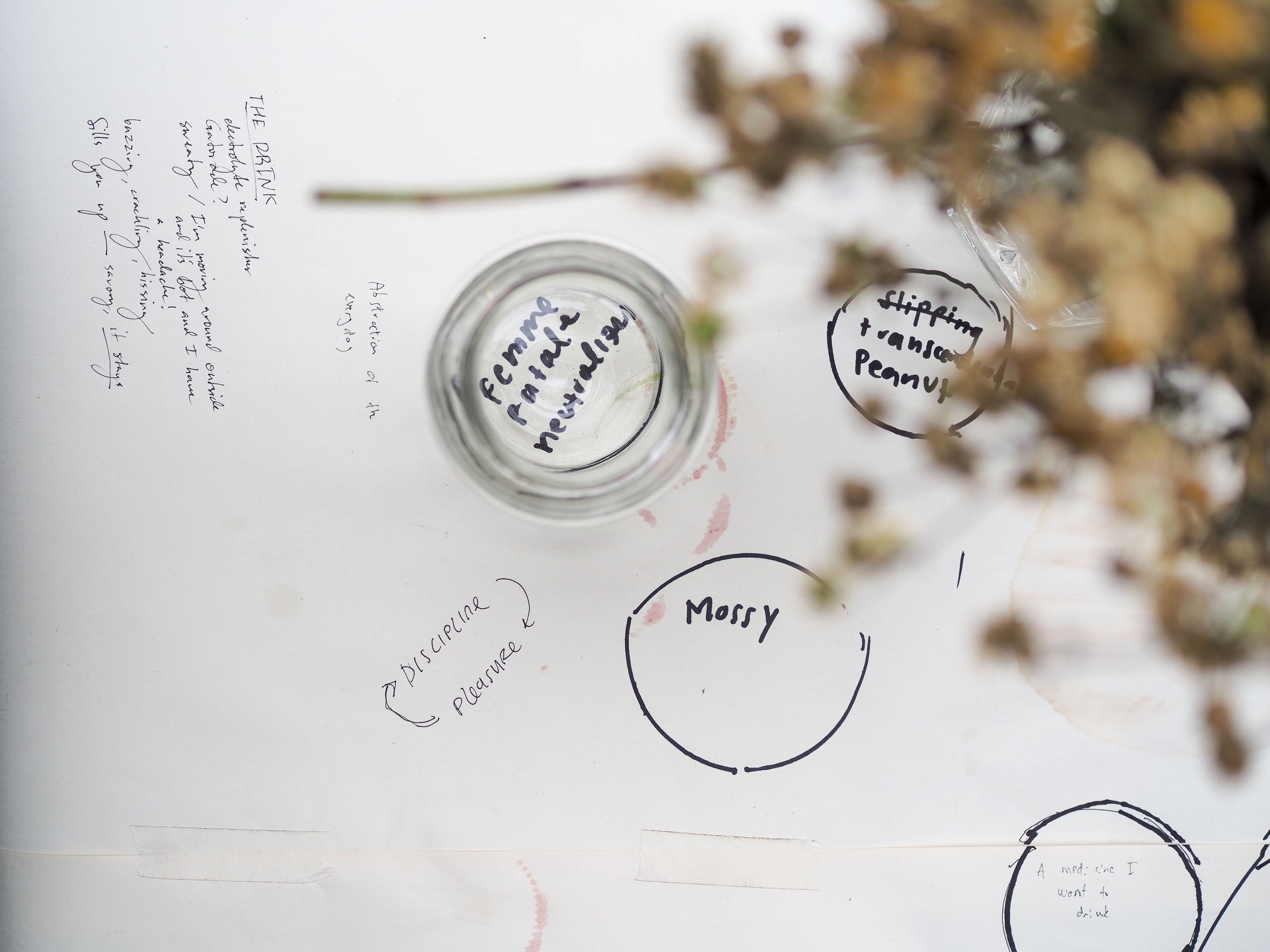

I then interviewed two creatives from a younger generation, working in both food and art, and organizing experimental gatherings centering both. One was poet and farmer Mallika Singh in Albuquerque and the other, artist and homemaker Tsohil Bhatia from the Red Flower Collective in New York, a food research and eating collective that hosts communal meals in borrowed kitchens. Interested in communal and social art practice, food was central to their conceptions of study, collaboration and politics.

At the end of all these conversations amidst mesas and over green chile and hours in Beinecke boxes, I tried to situate myself. What conditions enabled me, also a woman and a writer, to see meals as a site of “poetic imagination”, a term I use by way of Robin D. G. Kelley. Kelley likens great poetry to radical politics, naming poetry the effort to see the future in the present and imagine a new society. I came to this project invested in a meal’s ability to do the same, evoking hope, desire and dreams of a more satisfying future. I leave with larger questions about where this orientation itself comes from and who is allowed it. I wonder now, where does poetry come from? Eileen Myles says we write poems from our “metabolism.” Zadie Smith says there is no great difference between writing novels and making banana bread, they are both just things to do. Regardless, food enriches this inquiry.